Ever since I was a baby, I have been an incredibly picky eater. Certain textures made me vomit, and if someone made a smoothie and I walked into the kitchen, I would begin to cough and gag. My diet as a child consisted of buttered pasta, dino chicken nuggets, and broccoli. I loved milk but I hated all fruit and most vegetables. I was small for my age and underweight for many years. However, the worst of my peculiar digestion issues was heartburn. If I ate too much pasta, or ate it too fast, I would get horrible heartburn that made me feel like I couldn’t breathe. It was either this excruciating heartburn or a horrible stomach ache that lasted for hours.

My parents, understandably alarmed, took me to my first doctor – a gastroenterologist – around the age of six. A gastroenterologist is a doctor that specializes in the gastrointestinal track. He performed my first ever endoscopy, a procedure in which a patient is anesthetized, place a tube down your throat, and then place a camera down the tube to observe your digestive tract. Normally, the doctor will also take a biopsy for further analysis.

The doctor gave me some fiber and set up a follow up appointment, hoping that I just needed to adjust my diet and everything would move smoothly. We left the doctors office hopeful.

Unfortunately, no changes occurred in my symptoms, so my mom searched for a new doctor for a second opinion. We were recommended a doctor by a family friend who had a similar experience to mine. It took us a little while to get an appointment with him, but eventually we went in for our first visit. When the doctor came in, I had a horrible stomach ache and was draped over a seat. He came in, assessed me, and suggested I get an endoscopy with him.

I did the endoscopy with him at Yale, and while it wasn’t my favorite experience, it did lead to my eventual diagnosis. After looking at my biopsy and images, I was diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis (E.OE.).

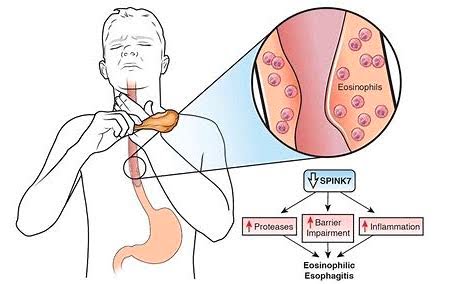

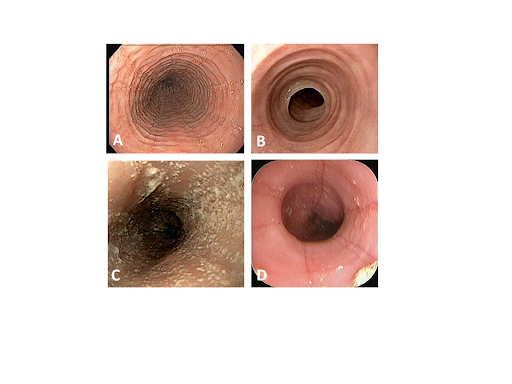

Eosinophilic esophagitis, is an inflammation of the esophagus (the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach), caused by a specific white blood cell – the eosinophil. The white blood cells can be a product of an irritant or allergic reaction. Is widely characterized by white rings or blotches within the folds of the esophagus. Typically it is diagnosed via an endoscopy – the procedure I described earlier – and a biopsy. The below image shows four different types of affected esophaguses. Each has the autoimmune disorder but at varying degrees.

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders, approximately 1 in every 2,000 individuals worldwide have E.O.E. The condition is most prevalent in Europe, Australia, and The United States. This raises the question of genetics relation to the disorder. According to the National Institutes of Health, “[m]ultiple studies have reported a strong familial component to E.O.E.”.. It is believed that the disorder is a result of multiple recessive genes that all amount to one result. The symptoms of the disorder can be managed by restrictive dieting and some medications, but there is no cure for the disorder.

In my experience, managing the condition was a classic trial and error. I tried to eliminate dairy for 6 weeks to determine if that was an irritant. I absolutely hated that experience because I loved cheese, milk, ice cream and other dairy products. I also tried two different medications designed to help with the symptoms and bring down my eosinophil levels. Both medications helped in their own way, but they also had side effects. Unfortunately this is the case for most people with the auto-immune disorder. While there are no cures for the disorder, there are a few clinical trials being done, but only a small number are trials for a cure.

Eventually, my eosinophil levels became close to healthy and I could go off medication. However, this was not the end for me. To this day, I still have to monitor my diet, get routine endoscopies, and I occasionally gag at various smells and textures. I will live with my disorder for the rest of my life which, while inconvenient, could be worse.

E.O.E., if left untreated, can worsen over time and cause narrowing of the esophagus and eventually stricture. Every year, around 4.6 per 1000 people die from eosinophilic esophagitis. Treatment is often expensive and inaccessible, especially if one does not have insurance. I am grateful that I could receive treatment, and I can’t help but feel empathy for those who aren’t as lucky.

It is imperative that the scientific and medical communities give more time and funding to finding a cure to eosinophilic esophagitis. A cure would change my life and the lives of thousands of others.